translation: theoretical models & art

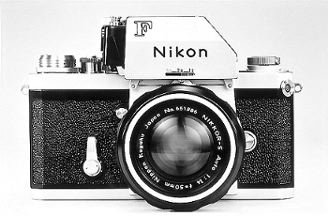

When I was doing still photography in the early 1970s, I had some friends who had studied design at Art Center in SoCal. Talking to them about visual art sparked an interest in the analytical principles of composition, color and gray scale. I spent many many hours reading about design, making extensive use of the public and university libraries. I tried to put design principles to work in my shooting but found it difficult to be analytical while working on location where the light and subject was in a constant state of change. The analytical approach seemed to kill something and produce stale results.

Recently I have been working on application of an ostensive-inferential communication model from cognitive linguistics to translation problems in Sophocles Electra. Looking over the the first speech of Orestes in the last few days I have been impressed by the skill evident in translations I have on hand; David Grene, Ezra Pound-Rudd Fleming and Ann Carson. Every time I think there is some important insight from an ostensive-inferential communication model that might be applied to the text while translating, I go and look at what these poets have done with Electra and discover that, for most part, they have applied these principles without having the formal theoretical model to work with. In other words, a good translator does a lot of things right intuitively without a formal theoretical framework.

On the other hand, the people who work from an analytical perspective using a formal theoretical framework often don’t produce brilliant translations. This is by no means a new observation but it has been impressed upon me in a new way. The theory is good to know when looking for failures in existing translations. But the theory does not in of itself produce good translation. You can study design until dooms day and never produce a work of art.

Recently I have been working on application of an ostensive-inferential communication model from cognitive linguistics to translation problems in Sophocles Electra. Looking over the the first speech of Orestes in the last few days I have been impressed by the skill evident in translations I have on hand; David Grene, Ezra Pound-Rudd Fleming and Ann Carson. Every time I think there is some important insight from an ostensive-inferential communication model that might be applied to the text while translating, I go and look at what these poets have done with Electra and discover that, for most part, they have applied these principles without having the formal theoretical model to work with. In other words, a good translator does a lot of things right intuitively without a formal theoretical framework.

On the other hand, the people who work from an analytical perspective using a formal theoretical framework often don’t produce brilliant translations. This is by no means a new observation but it has been impressed upon me in a new way. The theory is good to know when looking for failures in existing translations. But the theory does not in of itself produce good translation. You can study design until dooms day and never produce a work of art.