two interviews - Larry Hurtado & Woody Allen on Ingmar Bergman

I listened to two interviews on today. The first was an interview of Larry Hurtado. What is important about Larry Hurtado? He is the author of "Lord Jesus Christ: Devotion to Jesus in Earliest Christianity". That alone makes him important. Some people would probably say he is important for other reasons. You can find out what those are by reading other people.

Hurtado's comment on history is worth quoteing:

I would suggest that Hurtado has correctly diagnosed the disease but probably not found the cure. I will need to read more of what he has to say on this, but I don't think contemporary biblical-theological studies has ever recovered from modernism. I agree with Hurtado that the problem isn't one of liberals vs. traditionalists. The more conservative scholars who affirm theological orthodoxy are often thoroughly modern in both their thinking and methodology. Some have retreated into something like a premodern framework, but this doesn't really solve anything. The first thing the is required is an open repudiation of the modern framework, laying bare the evils, distortions and falsehoods that lay at the very foundation of the worldview that has been accepted for centuries as normative. Then perhaps it will be possible to find a way out of the nihilism of the post-modern.

The religion of Modernism brought with it horrors that even Joseph Conrad would not have imagined possible. Some of us who were born in the wake of that period of unpleasantness in Europe (1914-1945) had hardly learned to walk when we were introduced to the new reality delivered to us by the great minds of modernism, a cloud of death hovering over life on this planet. And for those of us who were living at "ground zero" this new reality completely undermined the pretensions of the modern. Anyone who would suggest that we should continue to look to the moderns to help us understand the most fundamental questions about existence was treated with the contempt that they deserved. Sadly, the revolt of the "sixties" against the modern lead many back into paganism and for those who turned to primitive new testament christianity, they certainly didn't look to "modern scholarship" for help along the way.

The second interview was with Woody Allen talking on Ingmar Bergman. This was a far better interview, not because Woody Allen is famous but because the interviewer knew what questions to ask and the discussion wasn't about trivialities. Woody Allen's thoughts on Bergman were -- this is going to sound silly -- they were profound. I cannot come up with a better way of saying it. Woody Allan knew what he was talking about, he went directly to the heart of the matter and he stayed there.

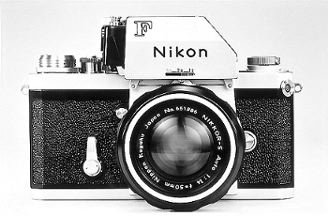

Why did I go and listen to Woody Allen talk about Ingmar Bergman? Today I was commenting on a series of portraits a man was posting. I told him his series reminded me of the photographer in The Passion of Anna (1970) who did portraits of people. When he was asked why he did portraits of people his response was something like "to capture the weakness in men's faces". That is not a direct quote. I couldn't find the quote. Not finding the quote meant that I spent all day with it in the back of my mind. Trying to reconstruct a line from a movie I saw only once in 1970.

Allen looks to "The Seventh Seal" as the essential Bergman film. This is the film that confronts modern man with the question left to us in that dark hour between the liberation of the camps and the beginning of the nuclear nightmare, the question "why is God silent?" left open and unresolved. For Woody Allen, the greatness of Bergman was his ability to raise the most fundamental questions with art, not just words, not just images but language and image, leaving a memory that still haunts us fifty years later.

Hurtado's comment on history is worth quoteing:

One intellectual issue that I had to ponder early on and across the years (and I hope successfully) was how to engage with integrity the historically-conditioned nature of the biblical texts while also affirming their significance and function as scripture for Christian faith. It seems to me that both extreme “liberal” and “conservative/fundamentalist” views actually agree implicitly on the same premise (which I regard as fallacious, or at least not incontestably true): If the biblical texts are really historically-conditioned they cannot be “word of God”. Recognizing the historically-conditioned nature of the biblical texts, the extreme liberal concludes they cannot really function as scripture. Affirming the texts as scripture, the fundamentalist tries to dodge their historically-conditioned nature. Worse yet, both views are fundamentally boring! It would take more space than available here to lay out my own view, but in essence I think that it is theologically necessary to treat seriously the historically-conditioned nature of the biblical texts, and this is precisely integral to their scriptural function.

I would suggest that Hurtado has correctly diagnosed the disease but probably not found the cure. I will need to read more of what he has to say on this, but I don't think contemporary biblical-theological studies has ever recovered from modernism. I agree with Hurtado that the problem isn't one of liberals vs. traditionalists. The more conservative scholars who affirm theological orthodoxy are often thoroughly modern in both their thinking and methodology. Some have retreated into something like a premodern framework, but this doesn't really solve anything. The first thing the is required is an open repudiation of the modern framework, laying bare the evils, distortions and falsehoods that lay at the very foundation of the worldview that has been accepted for centuries as normative. Then perhaps it will be possible to find a way out of the nihilism of the post-modern.

The religion of Modernism brought with it horrors that even Joseph Conrad would not have imagined possible. Some of us who were born in the wake of that period of unpleasantness in Europe (1914-1945) had hardly learned to walk when we were introduced to the new reality delivered to us by the great minds of modernism, a cloud of death hovering over life on this planet. And for those of us who were living at "ground zero" this new reality completely undermined the pretensions of the modern. Anyone who would suggest that we should continue to look to the moderns to help us understand the most fundamental questions about existence was treated with the contempt that they deserved. Sadly, the revolt of the "sixties" against the modern lead many back into paganism and for those who turned to primitive new testament christianity, they certainly didn't look to "modern scholarship" for help along the way.

The second interview was with Woody Allen talking on Ingmar Bergman. This was a far better interview, not because Woody Allen is famous but because the interviewer knew what questions to ask and the discussion wasn't about trivialities. Woody Allen's thoughts on Bergman were -- this is going to sound silly -- they were profound. I cannot come up with a better way of saying it. Woody Allan knew what he was talking about, he went directly to the heart of the matter and he stayed there.

Why did I go and listen to Woody Allen talk about Ingmar Bergman? Today I was commenting on a series of portraits a man was posting. I told him his series reminded me of the photographer in The Passion of Anna (1970) who did portraits of people. When he was asked why he did portraits of people his response was something like "to capture the weakness in men's faces". That is not a direct quote. I couldn't find the quote. Not finding the quote meant that I spent all day with it in the back of my mind. Trying to reconstruct a line from a movie I saw only once in 1970.

Allen looks to "The Seventh Seal" as the essential Bergman film. This is the film that confronts modern man with the question left to us in that dark hour between the liberation of the camps and the beginning of the nuclear nightmare, the question "why is God silent?" left open and unresolved. For Woody Allen, the greatness of Bergman was his ability to raise the most fundamental questions with art, not just words, not just images but language and image, leaving a memory that still haunts us fifty years later.

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

Subscribe to Post Comments [Atom]

<< Home